Extracting Sensitive Information from Aggregated Data - Part 1

One common challenge is convincing people that aggregate information can still qualify as personal data under the GDPR. By “aggregate information,” I refer to statistical summaries such as sums, medians, and means derived from a confidential dataset, or even the parameters of a trained machine learning model.

In this post, I start with a simple example: showing how sensitive personal data can be reconstructed from a series of SUM queries on a sensitive attribute. This technique is at the core of many advanced attacks on database systems, federated learning, or training data reconstruction in general. These attacks work for the same reason machine learning does—both rely on extracting patterns from data. I’ll show how the same techniques used to train a model can also be used to extract sensitive information from aggregate data. In a follow-up post, I’ll explore how an attacker can minimize the number of queries to reconstruct an entire dataset.

For the sake of illustration, consider the following hospital dataset.

| # | Name | ZIP | Gender | Blood sugar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Smith | 32453 | Male | 4.3 |

| 2 | Jeremy Doe | 43813 | Male | 5.2 |

| 3 | Susan Atkinson | 43765 | Female |

6.1 |

| 4 | Eve Brown | 32187 | Female | 3.2 |

| 5 | Joseph Sky | 33745 | Male | 7.1 |

| 6 | Alison Moon | 22983 | Female | 6.2 |

Here, ZIP and Gender (in green) are considered public attributes, while Name and Blood Sugar (in red) are private. We show how statistical queries (such as sums or averages) over Blood Sugar can potentially expose an individual's blood sugar value - even when each query is computed across multiple records.

Following SQL syntax, a query consists of a WHERE clause, which filters records from the dataset based on public attributes, and an aggregate function that summarizes a private attribute over the selected records. For example, the query SELECT SUM("Blood sugar") WHERE Gender = "Male" uses the predicate Gender = "Male" and the aggregate function SUM, returning the result 16.6 (the sum of blood sugar values for all males:

It is not hard to see that answering the following queries reveal the blood sugar level of the second record (Jeremy Doe), even though each query covers at least two records.

- Query 1:

SELECT SUM("Blood sugar") FROM Dataset; Result: 32.1 - Query 2:

SELECT SUM("Blood sugar") FROM Dataset WHERE Gender = "Female"; Result: 15.5 - Query 3:

SELECT SUM("Blood sugar") FROM Dataset WHERE ZIP > 32000 and ZIP < 35000 AND Gender = "Male"; Result: 11.4

To see why, notice that Query 1 and 2 reveal the total blood sugar level of all males (subtract the result of Query 2 from that of Query 1), and Query 3 selects only Record 1 and 5. Therefore, taking the difference of the result of Query 3 and the total blood sugar of all males, we obtain the exact blood sugar level of Record 2.

To make it more formal, let

- Query 1:

- Query 2:

- Query 3:

Or, with matrix notation:

where

Here,

Seemingly, solving this linear system for any unknown, without associating it with a specific individual (e.g., Jeremy Doe), should not imply a privacy breach under GDPR. According to GDPR, information is considered personal only if it can be linked to an identified or identifiable person. If the attacker only has access to public attributes (marked in blue), they likely cannot link the value of 438**. If this additional information is easily accessible, it could allow the attacker to determine Jeremy’s blood sugar value using the reconstruction attack described in this post. As a result, the outcomes of Queries 1, 2, and 3 may qualify as personal or sensitive data under GDPR when the attacker has "reasonable" access to the necessary background knowledge.

Which records can be reconstructed?

Given a linear system of equations

-

The system must be consistent, meaning that the vector

is a linear combination of the columns of . In other words, must lie within the column space of . This is verified by checking if , where is the augmented matrix formed by appending as a column to . -

The

th column of must be linearly independent of the remaining columns. To check this, remove the th column from and compute the rank of the resulting matrix. If the rank decreases, it confirms that the th column is linearly independent.

In the above example, each query was answered faithfully, hence the linear system is consistent. To illustrate the second condition, let's reformulate

This expression shows that vector

increases its rank by one:

import numpy as np

from numpy.linalg import matrix_rank

# Define the matrix A and vector b

A = np.array([

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0]

])

b = np.array([32.1, 15.5, 11.4])

for col in range(A.shape[1]):

print (f"Unknown x_{col+1} can be uniquely determined:",

matrix_rank(A) != matrix_rank(np.delete(A, col, axis=1)))

which produces:

Unknown x_1 can be uniquely determined: False

Unknown x_2 can be uniquely determined: True

Unknown x_3 can be uniquely determined: False

Unknown x_4 can be uniquely determined: False

Unknown x_5 can be uniquely determined: False

Unknown x_6 can be uniquely determined: False

However, this uniqueness does not apply to the other columns which appear multiple times in the matrix. After multiplying out these (linearly dependent) columns we have:

Since all the three column vectors are linearly independent in this reformulated version, we can uniquely determine their weights:

In general, if

If

In practice, when there are many possible public attributes to filter records and queries are chosen randomly, they are often linearly independent, increasing the risk of reconstructing private values.

Solving the equations

There are a couple of techniques to solve (or approximate) a linear system; any matrix decomposition technique (e.g., QR or LU decomposition) can be applied on the augmented matrix

where

The solution of this optimization problem has a closed form

For example, in numpy:

# Solve the system using NumPy's least-squares method (since A is not square)

x_prime = np.linalg.lstsq(A, b, rcond=None)[0]

print ("Solution:", x_prime)

and the output:

Solution: [5.7 5.2 5.16666667 5.16666667 5.7 5.16666667]

where Jeremy Doe's blood sugar level (

Incorporating background knowledge as constraints

The above solution can be made more accurate if we incorporate prior knowledge about the unknowns as additional constraints into the optimization problem. As long as these constraints are convex, efficient convex solvers can be used to obtain a better approximation of

import cvxpy as cvx

x = cvx.Variable(A.shape[1])

objective = cvx.Minimize(cvx.sum_squares(A @ x - b))

# First record is smaller than 5

constraints = [x[0] <= 5]

prob = cvx.Problem(objective, constraints)

prob.solve()

print ("Solution:", x.value)

and the output is:

Solution: [1.15961346e-04 5.20000027e+00 5.16666694e+00 5.16666694e+00 1.13998846e+01 5.16666694e+00]

This is quite silly as no one has a blood sugar level of less than 0.01. Let's add another constraint that all values must be larger than 3:

objective = cvx.Minimize(cvx.sum_squares(A @ x - b))

# Constraint 1: First record is less than 5

# Constraint 2: All records are larger than 3

constraints = [x[0] <= 5, x >= 3]

prob = cvx.Problem(objective, constraints)

prob.solve()

print ("Solution:", x.value)

The output is:

Solution: [4.06728662 5.20000018 5.1666669 5.1666669 7.3327138 5.1666669 ]

This looks much more realistic! This approximation is closer to the true solution

The private attribute

Handling many queries and records

Even convex optimization, including OLS, can become quite slow and memory-intensive for large datasets with many queries as they operate on the entire matrix

To address this, we present a technique based on stochastic gradient descent (SGD). Starting with a random initial solution to the equations, SGD updates it incrementally as a new query arrives. If the queries arrive randomly, the solution gradually converges to the final result for the equations while processing only one query at a time. This approach is particularly appealing in online scenarios where queries must be audited in real-time, or where storing the entire query set is impractical due to legal constraints or the sheer number of queries.

We aim to minimize the function

Since

However, in each descent step, we still iterate over all queries, making this approach computationally expensive and not better than other iterative techniques. To improve efficiency, stochastic gradient descent exploits that minimizing

where

The gradient is given by:

If we set the step size

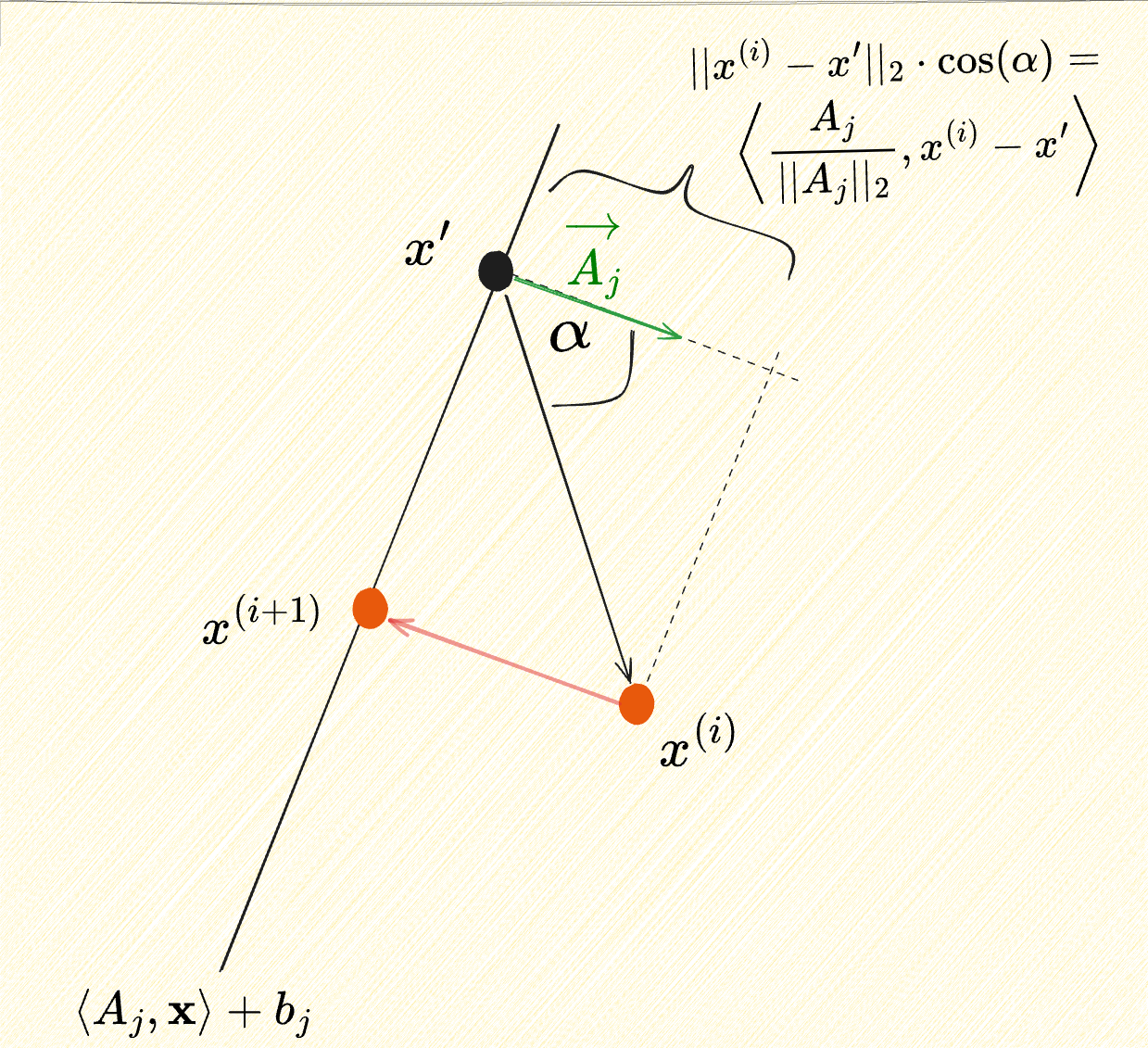

Kaczmarz’s method has an intuitive geometric interpretation: starting from an initial candidate solution

Let

The projectionof this displacement vector onto

and hence

for any

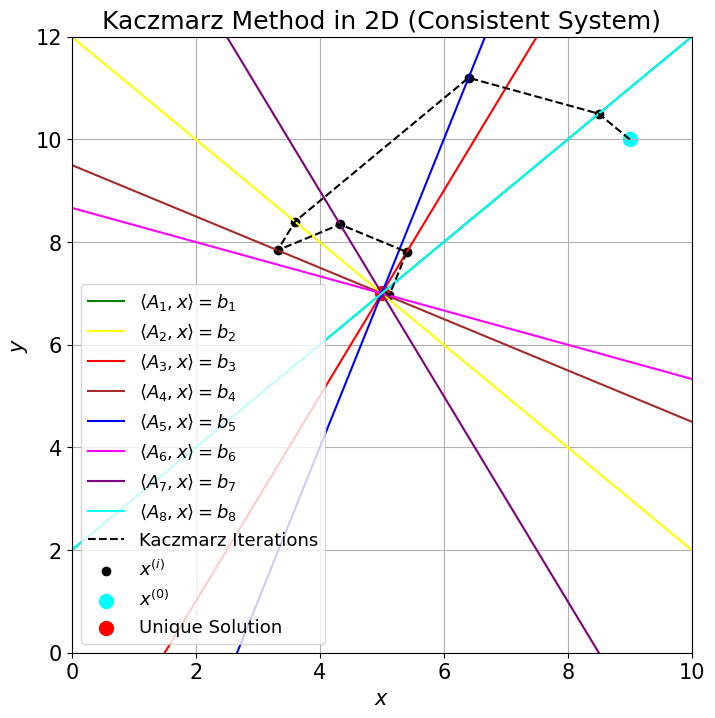

The steps of the process in 2D are shown in the figure below, where each equation is a line, and their single intersection point in the center is the unique solution to the whole system of equations. For consistent systems,

There are other variants of Kaczmarz's method that have been adapted even for inconsistent systems.

Adding constraints is also possible. For example, box constraints

where

Continuing our hospital example, suppose the blood sugar levels have lower bounds

import torch

A_t = torch.tensor(A).float()

b_t = torch.tensor(b)

# compute gradient wrt x_t

x_t = torch.zeros(A.shape[1], requires_grad=True)

# Box constraints (l: min blood sugar, u: max blood sugar)

l = torch.tensor([3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3])

u = torch.tensor([5, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10])

z = lambda x_t: l + (u - l) * torch.sigmoid(x_t)

learning_rate = 0.01

# Do 1000 SGD iterations

for i in range(1000):

# select one row from A

row = np.random.randint(0, A_t.shape[0])

# objective function

residual = torch.sum((A_t[row] @ z(x_t) - b[row])**2)

# compute gradient

residual.backward()

with torch.no_grad():

# gradient descent

x_t -= learning_rate * x_t.grad

x_t.grad.zero_()

print ("Solution:", z(x_t).detach().numpy())

that gives:

Solution: [4.0698786 5.2092214 5.165333 5.165333 7.3272643 5.165333 ]

This is close to the exact solution computed by cvxpy above!

Beyond linear queries

SUM, AVG, and COUNT are linear queries (i.e., linear functions of the attribute values) that can be audited using tools from linear algebra. However, auditing non-linear queries like MEDIAN, MAX, and MIN is more challenging. In fact, verifying exact disclosure for such queries may not even be feasible in polynomial time with respect to the dataset size

One approach is to approximate the missing attribute values using heuristics like SAT solvers. Another is to apply stochastic gradient descent (SGD), as discussed above, if the queries are "approximately" differentiable functions of the attribute values. However, if the queries are non-convex functions of the records, then SGD does not guarantee convergence to the global optimum, meaning we cannot be sure that the solution it finds corresponds to the actual attribute values. Nevertheless, as in machine learning, we can hope that the solutions found are reasonably close to the actual solution.

Reconstruction is everywhere

Extraction "attacks" have long existed in computer science, though they were known by different names. For instance, error-correcting codes reconstruct corrupted data by solving a system of equations where the unknowns are the corrupted bits, bytes, or blocks of bytes. Linear error-correcting codes, like Reed-Solomon or BCH, operate in a finite field and are widely used in applications ranging from satellite communications to redundant data storage or QR codes where noise can corrupt information. A significant part of signal processing deals with the fast processing of naturally redundant data, such as images or voice. For example, compressive sensing can reconstruct high-quality MRI images from just a few linear measurements, greatly speeding up MRI acquisition.

Similarly, regular model training in machine learning (or AI) is a form of extraction attack. Here, the unknowns are the model parameters, and each training sample forms an equation. The queries represent the model, and optimization techniques like stochastic gradient descent are used to solve these equations like above. Extraction attacks can also target machine learning models. Whether the goal is to reconstruct the training data (with the unknowns being the sample features) or the model itself (with the unknowns being the model parameters), the process boils down to solving a system of (typically non-linear) equations. These attacks are especially relevant in light of recent regulations, such as the EU AI Act and GDPR.

So, it’s no surprise that as machine learning keeps improving, more advanced data extraction attacks will also appear. In the next post, I’ll show how an attacker can minimize the number of queries needed for data reconstruction by borrowing techniques from signal processing.